Breaking Traditions

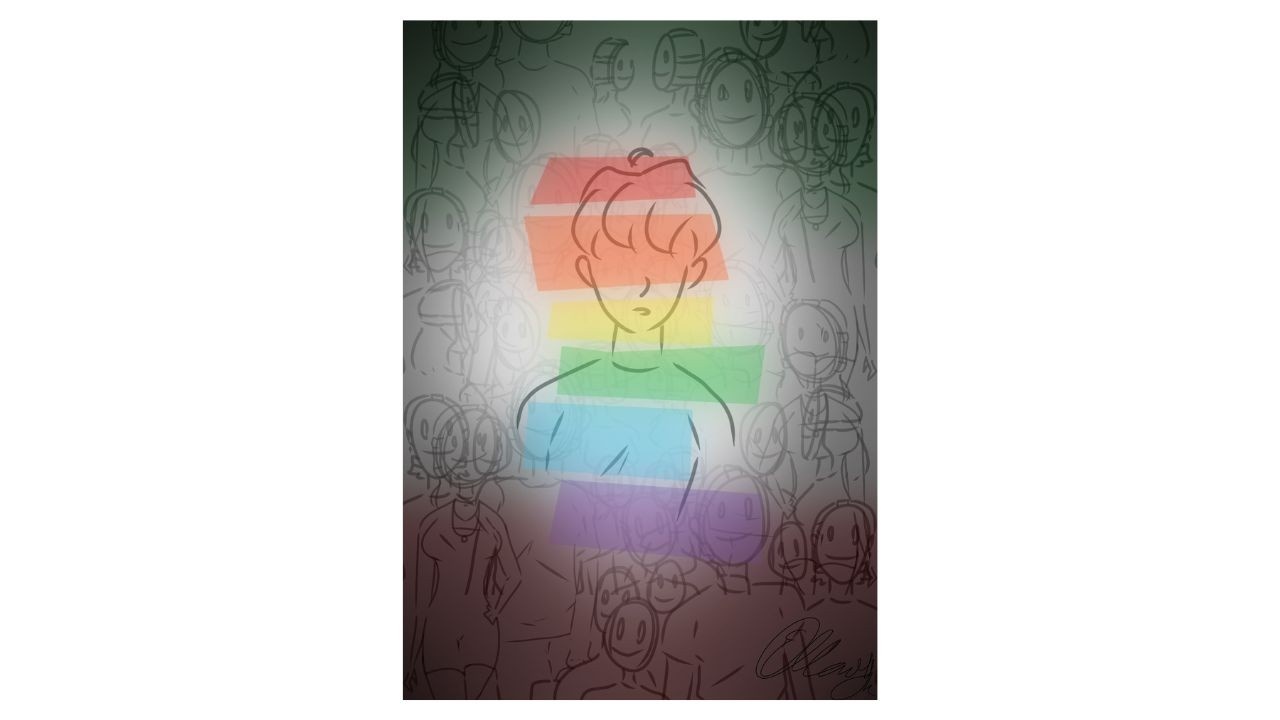

Dec 16, 2022This post was written by a CSUCI student, featuring artwork by Ellawyn Wood.

INTRODUCTION

"Machismo" in Spanish is a strong or aggressive masculine pride often associated with a man's role in a traditional family. Unlike a “quinceañera” which is a milestone for Latino girls in which they celebrate their transition from childhood to woman-hood, machismo is not celebrated at all. Instead, it is often inculcated at birth in boys. Like an instruction manual that you would receive with a product, machismo has its own set of rules and procedures on how to act like a “man.” Because machismo is so ingrained in Latino culture, it is viewed as the norm in the family structure. Therefore, any deviation from the rules and regulations of being macho is stigmatized.

Which brings you, the reader, to my story. Growing up I have learned very well how a man should act, what a man should say and what he should do. Moreover, growing up I have also learned that I could never act accordingly. As a result, I have struggled with my identity since childhood. First and foremost, I am a Mexican American born to Mexican parents who value culture and traditions. Secondly, I am a university student breaking stereotypes by pursuing higher education. Lastly and perhaps the most difficult to admit even today is that I am a gay man, fighting every day to free myself from the entrapment of the Latino patriarchal ideal of manhood that has tried to capture every essence of my being.

PART 1: SPANGLISH

Growing up I never thought I would lose myself, but I did. For me it happened suddenly. One day I realized I did not want to be the old me but a new me. A me that would help me navigate my life much easier than my old persona did.

I was born and raised in Oxnard, California. Oxnard is a beautiful city with great weather, amazing beaches, and famous for its strawberries. The best strawberries in all the land. However, Oxnard is also tainted by poverty and a high crime rate. Specifically, the south side of Oxnard, which is where I grew up. Here it is common to see carnicerias instead of grocery stores, street vendors selling corn smeared with warm mayonnaise and melted butter (a concept my American friends did not understand), and Mexican flags waving around town. The flags are not up as an act of rebellion but instead as an understanding among Mexicans. It is the symbol representing cultural unity in a community. My parents immigrated to this city from Mexico in search of a better life. They arrived here with a suitcase full of clothes, with little money and their cultural traditions, traditions they would instill in my siblings and me.

I am one of four children and I classify myself as the forgotten middle child. I knew early on I did not fit any specific mold. As the middle child of the family, that often meant I had bigger shoes to fill left by my older brother, Jim, and my older sister, Samantha. There is a ten year gap between them and me, which meant they were attached at the hip and there was no room for me. Synchronously being the middle child also meant leaving shoes for my younger brother Junior, who is two years younger than I am. To add to the burden of being the middle child of my family I simultaneously had to navigate the struggles of being a Mexican American in this country all by myself.

My native language is Spanglish, a mix of Spanish and English. I say this because Spanglish was regularly spoken at home. It was not always this way. I learned to speak Spanish first from my parents. They taught my siblings and me Spanish because it was the only language they knew. Learning to speak English was a result of interactions I had with my older siblings and watching television shows such as Barney, The Magic School Bus, and Clifford the Big Red Dog. Eventually, the two languages merged together to form a blob of what I now call Spanglish. For example, the Spanish word for parking is “estacionar.” At my house, however, we did not park a car or “no estacionavamos el carro,” but instead “parkeavamos el carro." Spanglish was my way of adapting from having to juggle between the two languages I heard all of the time. I was presented with the tedious task of having to be Mexican enough for my family and our traditions yet be as American as apple pie outside of my home with friends and the many other people I encountered that did not understand my culture. Often, I felt like a superhero, like the ones you see on television with a secret identity by day and fighting crime at night. Instead of crimes however, I was fighting stereotypes. My biggest battle was yet to come: education.

PART 2: SAMANTHA

To the world she is known as Samantha, to my parents she is “la niña,” but to me, she is known as a role model.

I will always remember the first time I was bullied for being Mexican American. I was in third grade and it was the first year I was enrolled in an all English speaking classroom. I was sitting with two other children who, like me, had trouble navigating the course because we had transitioned from only learning in Spanish. During our free time we liked to deviate from speaking English and would speak amongst each other in Spanish. “Cual es tu color favorito?” my friend Veronica asked. “Rosita,” I replied. As I was about to reciprocate the question, our conversation was cut short by another classmate named Sean. “Speak English you beaner!” he yelled. I looked at him confused. I did not say anything because I was too young to understand what “beaner” meant. Veronica pulled me closer and whispered to me the definition of the racial slur he had just called me, and my jaw dropped. I looked back at Sean who was now giggling with a group of friends but still said nothing.

I went home that day embarrassed. The insult replayed in my head like a broken record. “Beaner, beaner, BEANER!” I did not understand why I was so bothered by that boy’s insult; it wasn’t like I flaunted my culture around saying, “Hey, look at me! I am Mexican!” Not that there is anything wrong with that. If I had to guess, it was the fact that I had never thought of being Mexican American as a bad thing. For the first time in my short life, I was embarrassed by my culture. Looking back at that incident, I wish I would have known then what I know now about being a Mexican American in this country. I thought all of my problems would go away if I was not Mexican. Furthermore, I thought to myself - I’ll just pretend not to know Spanish and the bullying will stop. Later that night my sister Samantha must have noticed I was acting differently because she asked me, “What’s wrong?” "Nothing,” I replied. I was not a good liar and she knew because she asked me again. “I don’t want to be Mexican anymore," I blurted out. “What? What do you mean you don’t want to be Mexican anymore?” I told her about the incident. I paused after as if waiting for some sort of consolation but all she did was laugh. I started to cry, but her laughter only grew louder. “Consider yourself lucky,” she said. “Most people only know one language, but we know two.”

I never thought of being bilingual as good or bad, even before this incident. My sister always knew what to say to comfort me. She would often tell me, “Be free to be whom you want to be.” She was the person that understood me the most in ways I was still too young to understand myself. On occasion, I would humorously tease her for being the favorite of our family as a result of being “la niña,” the only girl amongst my siblings. Nevertheless, I always looked up to her. My parents will tell you she was an amazing daughter that never gave them any trouble. Her husband would say he never loved anyone more than her. I could tell you that she is the reason that I am who I am today. My motivator for pursuing higher education is her. When I was younger, she was the first one I would show my report cards to because she was excited to see them. Still to this day, I don’t take flowers to her grave. I take accomplishments.

PART 3: BREAKING FREE

Growing up I have learned very well how a man should act, what a man should say and what he should do. Moreover, growing up I have also learned that I could never act accordingly.

Despite being born in America where different people, views, and cultures intertwine, I was expected to only follow mine. Growing up, expectations were clear. They were black and white with no grey areas. Family is important in every culture; however, it is especially important in Mexican culture. Being one of two boys in my family, I was expected to act like a “traditional” boy in every sense of the word. It was not enough that my brothers and I were expected to grow up to be men but needed to exceed that expectation by being “machos,” which is far stronger and masculine.

When I was in first grade, on the very first day of school our teacher had each student choose a pencil box. One by one she called us by our names to the stack of different colored pencil boxes laid out on her desk. When it came to my turn, I walked up and grabbed a pink box not thinking much about it. I was excited to place my crayons and pencils inside. The teacher even gave us stickers to decorate it. I carried it home like a baby in my hands making sure I was keeping it as pristine as possible. As I got home, my mother greeted me and said “Como te fue el la escuela mijo?” “Bien,” I replied. I showed her my pencil box and told her the teacher gave each of the students one. She looked at it without saying a word and walked away. Had I done something wrong, I thought to myself. Her reaction left me confused as if I were in trouble.

Later that night I heard my mother and father having a conversation about the box. I couldn’t make out exactly what was said, but the next thing I saw was my father storming over into the living room looking for my backpack. He grabbed the pencil box and said, “esto es de niñas!” and he threw it in the trash. I sat there frozen unable to speak, tears rolling down my face. Being macho means being a man without the slightest hint of femininity and to my father that pink pencil box was a hint of femininity. It was from that point on that I knew I could never be myself in front of my family. I had to hide what and whom I liked because I knew it did not align with our patriarchal culture.

The day I finally came out to my mother was probably the scariest day of my life. How would she react? Would she yell at me? Would I be kicked out of my house? All these thoughts ran through my head. One night we were in the kitchen while she was cooking, and I was mustering up the courage to tell her. I could see her hand stirring a pot of arroz con leche. I began to perspire as the sentence was forming in my throat. My heart started racing faster and faster as I opened my mouth. “Mom, soy gay,” I finally blurted out. I felt a sense of relief as I could finally breathe again. She looked up at the kitchen wall in front of her; she had stopped stirring. I was waiting for a reaction. We both stood there quietly for what seemed like an eternity. She continued stirring the pot without saying a word. It would be a week before she finally spoke to me again.

I have learned many lessons throughout my life. Growing up as a minority and having to navigate my life as a Mexican American has taught me FEAR. Fear because of all the racial violence minorities face in this country. Furthermore, growing up as a gay man in a patriarchal Latino culture has taught me SHAME. Shame because being gay is the equivalent of being weak, the opposite of being macho. I must admit I have had days when I was hurting, thinking to myself maybe it’s true, maybe it is shameful to be different. However, I have now realized that I am not different, I AM ME. People have their opinions and beliefs, and that is ok, but I WILL NEVER APOLOGIZE FOR BEING WHO I AM. From this, I have learned STRENGTH. Strength to finally break free.